Nitrogen is the lifeblood of a corn plant, says LG Seeds Agronomist Justin Schneider. When levels of this key nutrient run low, it can have a major impact on performance. Unfortunately, it’s also extremely mobile, which can make it difficult to manage corn nitrogen requirements — especially in growing seasons marked with heavy rains.

With that said, the No. 1 thing Schneider recommends after a rain event is to not jump to the conclusion that yellowing corn means nitrogen supplies have been exhausted. Nitrogen isn’t always the culprit — and if it is, there’s likely still time to supplement nitrogen.

What causes the loss of nitrogen in the soil?

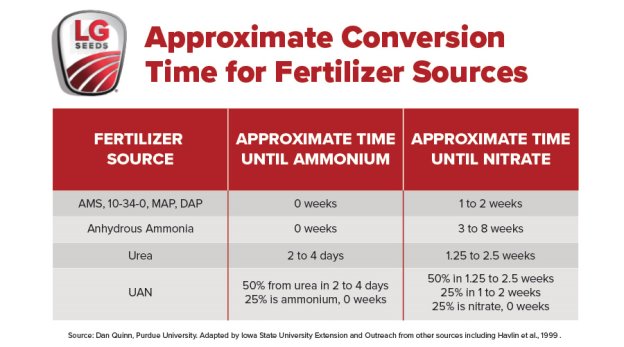

The temperature, texture and drainage of the soil all come into play when calculating nitrogen loss, as well as the fertilizer type and form of nitrogen. “Nitrogen needs to be in the nitrate form to be lost to leaching or denitrification,” Schneider explains. “If it’s still in its organic or ammonia form, it can’t be lost.”

Nitrogen converts to nitrate quickly, with that timeline again hinging on numerous factors like the type of nitrogen, soil type and temperatures. Nitrogen inhibitors can slow down the nitrate conversion process.

An extension report from Iowa State University details, “The conversion process of ammonium to nitrate can be delayed up to two weeks by using a nitrification inhibitor, while urea conversion to nitrate can be delayed up to 10 days by using urease inhibitors.”

The two primary ways nitrogen loss in corn occurs are via leaching and denitrification of soil. With leaching, nitrates move below the root zone due to drainage within the soil profile. Leaching can be amplified by heavy rainfall events, with rapid drainage patterns like those found in tile-drained fields upping that risk.

Denitrification, on the other hand, is a biochemical reaction where bacteria in oxygen-depleted soils transform nitrogen into gas. Finely textured or sandy soils that are poorly drained and tend to pond are prone to denitrification. Denitrification typically gets underway after two or three days of soil saturation, with higher soil temperatures accelerating that reaction.1

“Research from the University of Illinois shows warmer soils accelerate denitrification losses, with daily nitrate loss of 4% to 5% estimated when soil temperatures are above 65 degrees,” 2 Schneider points out.

Scout for nitrogen deficient corn

“When corn in low spots yellows or growth is stunted following a rain event, it’s easy to fret the plant is running out of nitrogen,” Schneider says. But that’s typically not the case. Up to the V6 growth stage, the corn plant typically only uses 20 to 25 lbs. of nitrogen, he says.

“If you received 1 to 2 inches of rain, nitrogen deficiency isn’t typically something to worry about,” Schneider details. “If you received 5+ inches of rain in a few-week period, that’s a different story. Supplementing may be necessary.”

He recommends farmers scout fields, keeping an eye out for the dull green color that signals nitrogen stress. “By the time you notice nitrogen deficiency in corn plants, you’ve likely already lost some yield potential,” he says. Soil nitrate testing and leaf tissue testing are other tools farmers can use to gauge nitrogen availability and corn’s nitrogen uptake.

Scouting should also include evaluations of yield potential since that factors into decision-making about any supplemental nitrogen applications. How initial application rates compared to maximum return to nitrogen rates should also be considered.

Supplemental nitrogen applications

“Keep in mind, corn needs around half of its nitrogen after it tassels,” Schneider says. That means farmers have some time to supplement, if needed.

“Most areas won’t need a high-clearance sprayer yet,” he says. “Farmers could put Y-drops or some drop nozzles on self-propelled sprayers to supplement nitrogen.” They can also add a bit of nitrogen with any fungicide applications.

Another tip Schneider shares is to apply 10 to 20 lbs. of extra nitrogen to early planted acres, knowing those fields will likely see a few more rains than those planted later in the spring.

“If possible, it’s best to split apply nitrogen fertilizer,” Schneider concludes.

Don’t forget about sulfur

“Sulfur is nitrogen’s partner in crime. It’s the Robin to nitrogen’s Batman,” Schneider says. “Sulfur enables corn plants to be more efficient with the nitrogen that’s available.”

Like nitrogen, sulfur can leach through the soil profile when conditions are wet. Therefore, Schneider encourages farmers to make sure they’re using proper sulfur rates and supplementing, as necessary.

Looking for more support dealing with any in-season challenges? Contact your local LG Seeds agronomist.